Opinion by John Patkin and Frank Wilcox. Digital radio has a future in Australia for the wrong reasons – mobile data is too expensive and plans for a National Broadband Network seem to be in the hands of bickering politicians.

The terrestrial radio industry has a few years’ breathing space until Internet Service Providers and telecoms bring data charges down to a level where streaming audio is cost effectively provided through their ubiquitous transmitters. Already used by subscribers for calling, texting and browsing, telecoms could co-operate with the music industry in a deal that bypasses radio broadcasting regulations but ensures listeners will be offered free content based on their locality which will be supported by advertising. Mobile networks in Hong Kong are doing something similar by partnering with broadcasters to stream live unmetered content. This model will do away with DAB+’s radio with pictures and the need to carry an extra device because radio must be portable and convenient to appeal to the younger generation.

The switch to DAB+ is creating market confusion and increasing costs with a single system confined to a limited space. Some analogue stations simulcast on DAB+, some have a watered-down version of their primary station and some have a bunch of new channels. More choice is going to lead to increased costs for existing broadcasters. The cost of setting up and maintaining DAB+ facilities, even if they are shared, has to be a thorn. Telcos on the other hand have tens of thousands of users who pay for that and their reach is far greater with hundreds of repeaters. Telcos are motivated to improve and upgrade their service due to competition between smartphone manufacturers and software developers who are constantly fighting for market share. Terrestrial radio has been sidelined in this competition.

DAB+ tuning chips, even though their cost is negligible, aren’t built into smartphones like FM ones so a second device is needed to tune in. Even if the DAB+ chip is built into a smartphone, there’s still the issue of an antenna. You can’t listen to FM or DAB+ over a wireless Bluetooth connection while you’re on the move or use the inbuilt speaker unless you have a wire attached to headphones acting as an antenna. And smartphones are getting better. It’s possible to listen to any station with an online presence while swimming with waterproof Bluetooth headphones. Imagine what this means for surfers, boaties, and those who work outdoors. Securing this segment will become increasingly important as the workforce continues its transition to quiet white collar environments. Terrestrial broadcasting and its cumbersome technology is affecting radio’s future because consumers growing-up with smartphones will expect a seamless system.

The strength of the Internet needs to be fully embraced as the small problems with delivery and reception will diminish as technology improves. Despite the strength of the Internet and the portability of smartphones, broadcasters appear to have responded to the challenge of the Internet by treating it as a distant platform with apps that allow users to choose content. Again, the abundance of choice dilutes core brands and wastes valuable resources. Broadcasters should focus on their primary product and embrace streaming radio with a direct feed of their terrestrial service instead of inventing a new one to compete with established channels and services.

Some industry leaders are making decisions with the belief future users will want to carry around a separate device. They also think that after years of opting for their own choice in audio and ignoring terrestrial radio, they are going to win back youths by asking them to listen to the same stations as their parents in promos on stations they don’t listen to. The sad truth for Australian radio is that it is being forced into investing into DAB+ in an argument supported by personal opinion and dodgy figures.

The industry is supporting its position by citing figures showing a growing number of DAB+ receivers are being installed in new vehicles but surely the future of in-vehicle communications has to be more than one way? The end-game may morph the Kindle model where a mobile internet connection will ensure seamless updates. Such connectivity will update the vehicle’s software and also provide streaming data such as maps, where to get the cheapest fuel and a whole bunch of radio stations. Local weather and traffic are available via a variety of free apps that use a negligible amount of bandwidth and listeners can tune into local stations if they provide suitable content. Radio networks have been inserting local content such as news, weather, traffic, sports and stocks for years but it too is being challenged by the Internet as social media updates east coast programmes before their time-delay broadcast in central and western Australia.

Broadcasters wanting a future should be working with telcos to ensure integration into the internet environment. It’s much cheaper, potentially more profitable and will ensure telcos provide good content. The alternative is to allow telcos to go it alone by hiring talent away from the radio industry. This is not a new model. Hong Kong Internet Service Provider Netvigator has its own free-to-air all TV news channel along with paid services. The modem is available free of charge even if households don’t subscribe to any pay channels. Netvigator’s sister company PCCW streams some media without charging mobile subscribers.

Critics are right to question the cost of mobile-delivered content, its costs and reliability in Australia. But that’s this week. Changes in technology, increased competition and consumer perception through globalisation will add pressure on telcos to offer more for less.

Countries such as Ghana have bypassed fixed lines and chosen mobiles instead; Singapore closed down its DAB+; and Hong Kong’s first sole DAB+ operator shut and reopened before its official launch. Separate research reports in the United States and Hong Kong have found that the Internet has moved past radio as the most used medium, is ready to challenge TV and younger people are using handheld media more than older groups. In research among Hong Kong teenagers, one focus group member who said he listened to the radio was ridiculed by other participants for an activity they associated with their grandparents.

In some cases, the growth of DAB+ is being used to pigeon-hole dissenting views and democracy due to its limited reach. Vietnam, with a long list of human rights violation and the blocking of the Internet, has plans to introduce DAB+. Telco delivered content is much harder to control and, as we have seen in the Arab Spring, restricting access to phones attracts international condemnation.

The Hong Kong government has come up with a convoluted plan of using DAB+ for community radio but there are no plans to close down the popular Chinese language FM stations. Instead, minorities, already stuck in the digital divide have to pitch programme ideas to a committee managed by the city-state’s government-funded public broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK). If successful, non-governmental organisations (NGO) and community groups will receive a grant to make programmes that might be broadcast on one of RTHK’s digital channels. Most of the costs will go to production and it so happens that RTHK is willing to provide production services at a fee. There are a few dollars left over to pay volunteers. That’s fine for well funded NGOs, but small groups staffed by volunteers from grassroots communities who work long hours and use more time taking public transport will really suffer. They will be producing “free” programming for a government-funded broadcaster which can pay presenters and producers around US$8,000 per month. The same volunteers from minority groups might comprise full-time journalists and social workers who can produce compelling content yet not be rewarded in the same way. Worse still is there content will be heard by few people on DAB+.

As in Australia, DAB+ receivers are relatively expensive with some smaller models a little less than the price of a smartphone. Telcos can sweeten subscriber contracts by amortising the cost of smartphones and offer attractive deals to regularly upgrade handsets. The cost of more sophisticated and expensive DAB+ receivers with display screens may contribute to the digital divide and weaken radio’s core strengths of portability and immediacy. This begs the question ‘why not just watch TV or leave it on in the background?’

Embracing a relationship between telcos and terrestrial radio license holders will also benefit the sale of air-time and reduce governmental control. Stations will have access to an unprecedented array of research data. Apart from being able to inform advertisers who is listening to spots, data will also show typical listening habits with full demographics and where they are tuning in. Lack of regulation will also allow full freedom of speech and creativity that restricts stick-in-the-mud operations.

In order to ensure radio’s future as a culture and maintain its strength as a key medium, broadcasters should consider adopting the following action plan.

1. Maintain analogue for current audience

2. Partner as content providers with Telcos immediately

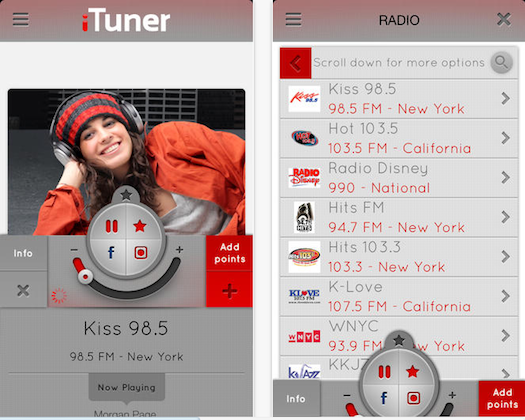

3. Limit segmentation by reducing Internet channels and reinforce brand through key free smartphone apps such as TuneIn

4. Have a back-up app in case TuneIn fails

For some, such a plan is a painful and bitter pill, especially companies that have invested in a variety of technologies in the true spirit of ‘broadcasting’. If this is not the solution in a climate where radio advertising is falling, three free to air TV channels are on tenterhooks and the Internet is raking in cash, then let it be the start of some brainstorming that ensures that there is a semi-structured platform for the convenient sharing of ideas with live audio.

John Patkin is a Hong Kong-based media researcher

Frank Wilcox is a consulting broadcast engineer

Thanks for this excellent column, gentlemen. Such a dynamic envoronment, you wonder if terrestrial radio can survive. Another aspect holding back DAB+ in Australia is the limited number of models of digital receivers available. I have searched in vain for a simple pocket receiver similar in size to the SONY ICF-S10MK2 receiver I have had for several years now. Alas, the retailers seem obsessed with selling larger models that have a "heritage" style and look, assuming that only older listeners would be interested in the medium. Either that or the DAB+ radio available is of the old AWA "swinging brick" sizing. The attraction of having all available stations on one band on a receiver I can slip into a pocket to take on a walk or to a sports event is a major attraction for me. Now folks, just sell a small handset a la the one noted above and sales just might pick up leading to better revenue for the broadcasters. Another recent fly in the ointment is the High Court ruling (September 2013) that is resulting in many stations pulling their Internet streaming lest they cop further performance fees. This decision may do more harm than good for all concerned.